The second volume of the excellent Benjamin Justice detective series by John Morgan Wilson, Revision of Justice, was published in 1997, just a year after the first volume, which had won the Edgar Allan Poe Award. The series is being reissued by ReQueered Tales, a publishing house specializing in issuing out-of-print gay books. Revision of Justice was re-released a few months ago. In the preface, the author confesses that the book seemed rushed after the previous one and describes it as « clumsily structured, self-indulgent, thinly researched yet overwritten, and replete with unconvincing action and egregious errors of fact. » He took advantage of the reissue to significantly revise it, he says.

I have just read the original edition where these flaws did not seem obvious to me. Benjamin Justice is a former star reporter for the Los Angeles Times. His professional rise was abruptly halted when the Pulitzer Prize he had won was revoked after he admitted that part of his reporting was fabricated. He sank into depression and alcoholism, from which he is slowly recovering when the series begins, set in mid-1990s Los Angeles. His former editor, also tarnished by the scandal, has landed at the less prestigious Los Angeles Sun. Despite this, he maintains friendship and respect for Justice and offers him to work with one of his most promising journalists, Alexandra Templeton.

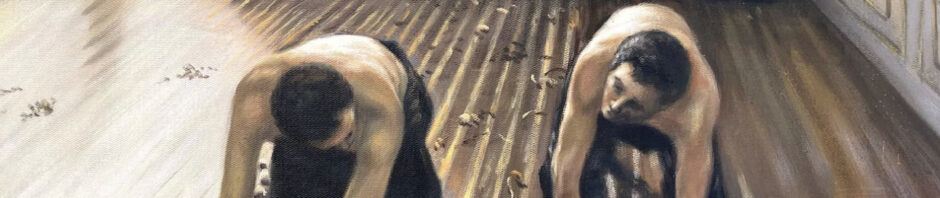

In Revision of Justice, they investigate the death of a young aspiring screenwriter in the Hollywood film scene. Things get complicated when Justice fall in love with Danny Romero, a young man who shared an apartment with the man found dead. Danny is HIV positive and is struggling with daily life issues. Justice offers to help by housing him at an older gay couple’s, Maurice and Fred, deeply involved in supporting AIDS patients, with whom he has a longstanding friendship and from whom he rents a flat on top of their garage. This is how we get presented with a small critical anthology of gay films:

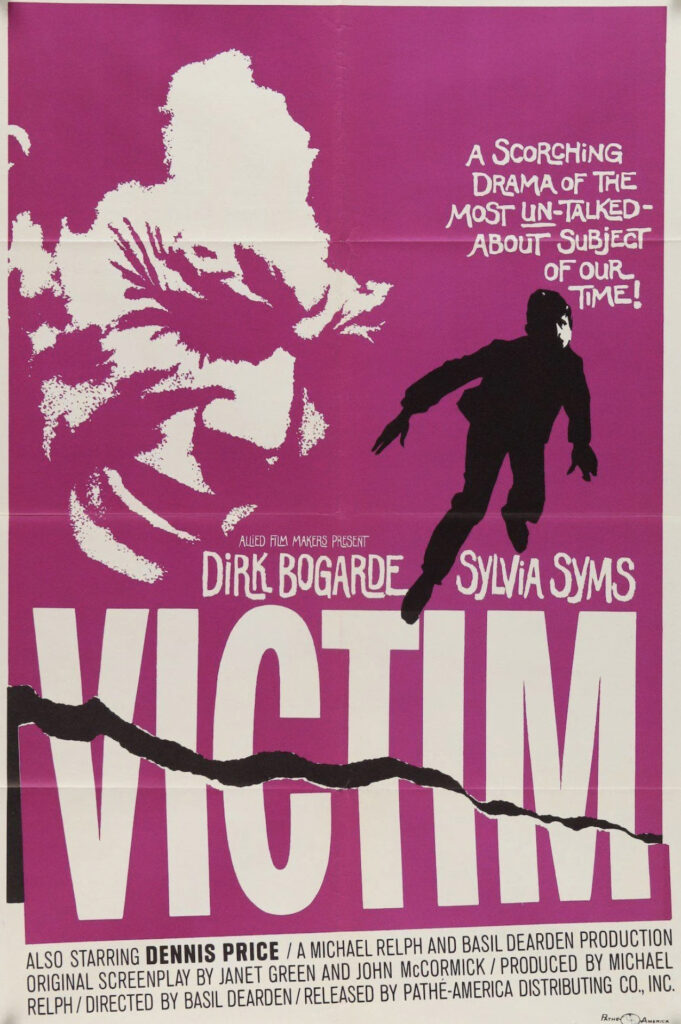

« Maurice pointed out the TV set and VCR, and a modest collection of feature films that featured humane portrayals of gay male characters – Ernesto; Maurice; Victim; Another Country; Sunday, Bloody Sunday; Victor, Victoria; La Cage aux Folles; Parting Glances; My Own Private Idaho; Philadelphia; Longtime Companion; Beautiful Thing. Films that Maurice found heavily flawed by homosexual stereotype or veiled with homophobia – Death in Venice, Midnight Cowboy, Partners, A Different Story– were excluded from his collection. Anything by William Friedkin was banned – Maurice could not forgive the director for Boys in the Band and Cruising – and Making Love was missing because Maurice found it as boring as it was well-meaning. His generous demeanor masked a ruthless unyielding critic. »

I leave it to you to complete the list with films released after 1995, the year in which the novel takes place. I have not seen all these movies, but I consider Victim, the 1961 British movie directed by Basil Dearden and starring Dirk Bogarde, one of the most moving and best gay movies ever released.

Le deuxième volume de l’excellente série policière Benjamin Justice de John Morgan Wilson, Revision of Justice a été publié en 1997, à peine un an après le premier qui avait obtenu le Edgar Allan Poe Award. La série fait l’objet d’une réédition chez ReQueered Tales, une maison d’édition qui se spécialise dans la publication de livres gays épuisés. Revision of Justice est ressorti il y a quelques mois. Dans la préface, l’auteur confesse que le livre a paru trop rapidement après le précédent, et est « mal ficelé, mièvre, d’une écriture trop recherchée, truffé de scènes d’actions peu crédibles et d’erreurs factuelles et repose sur une documentation bâclée. » Il a profité de la réédition pour le revoir de façon significative, nous dit-il.

Je viens de le lire dans l’édition originale dont les défauts ne m’ont pas semblés évidents. Benjamin Justice est un ancien reporter vedette du Los Angeles Times. Son ascension professionnelle a été interrompue net lorsque le prix Pulitzer qu’il avait gagné lui a été retiré après qu’il eut reconnu que le reportage était en partie inventé. Il a sombré dans la dépression et l’alcoolisme dont il se relève peu à peu lorsque commence la série, dans le Los Angeles du milieu des années 1990. Son ancien rédacteur en chef, lui aussi touché par le scandale, s’est recasé dans le moins prestigieux Los Angeles Sun. Il lui a gardé amitié et respect et pour lui venir en aide, lui a proposé de travailler avec une de ses journalistes les plus prometteuses, Alexandra Templeton.

Dans Revision of Justice, ils enquêtent sur la mort d’un jeune aspirant scénariste dans le milieu du cinéma hollywoodien. Les choses se compliquent lorsque Justice tombe amoureux de Danny Romero, un jeune homme qui partageait un appartement avec l’homme trouvé mort. Danny est atteint du sida et a du mal a gérer le quotidien. Pour lui venir en aide Justice lui propose de l’héberger chez un couple de vieux homosexuels, Maurice et Fred, très impliqués dans le soutient aux malades du sida, auxquels le lie une ancienne amitié et chez qui lui-même loue un appartement. C’est ainsi que l’on découvre une petite anthologie critique de films gays :

« Maurice désigna la télévision et le magnétoscope, et une modeste collection de films dont les protagonistes gays sont présentés de façon positive – Ernesto; Maurice; Victim; Another Country; Sunday, Bloody Sunday; Victor, Victoria; La Cage aux Folles; Parting Glances; My Own Private Idaho; Philadelphia; Longtime Companion; Beautiful Thing. Les films qui, selon Maurice, présentaient des personnages stéréotypés ou avaient des relents d’homophobie – Death in Venice, Midnight Cowboy, Partners, A Different Story – ne figuraient pas dans sa collection. Les œuvres de William Friedkin étaient bannies – Maurice ne pardonnait pas au metteur en scène de Boys in the Band and Cruising – enfin, Making Love était absent parce que Maurice considérait le film aussi ennuyeux que pavé de bonnes intentions. Son allure bienveillante masquait un critique impitoyable. »

À vous de la compléter avec les films sortis depuis 1995, année au cours de laquelle se déroule le roman. Je n’ai pas vu tous ces films, mais Victim, le film britannique mis en scène par Basil Dearden avec Dirk Bogarde, est sans doute un des films gays le plus émouvant et le meilleur jamais réalisé.

Gabriel François